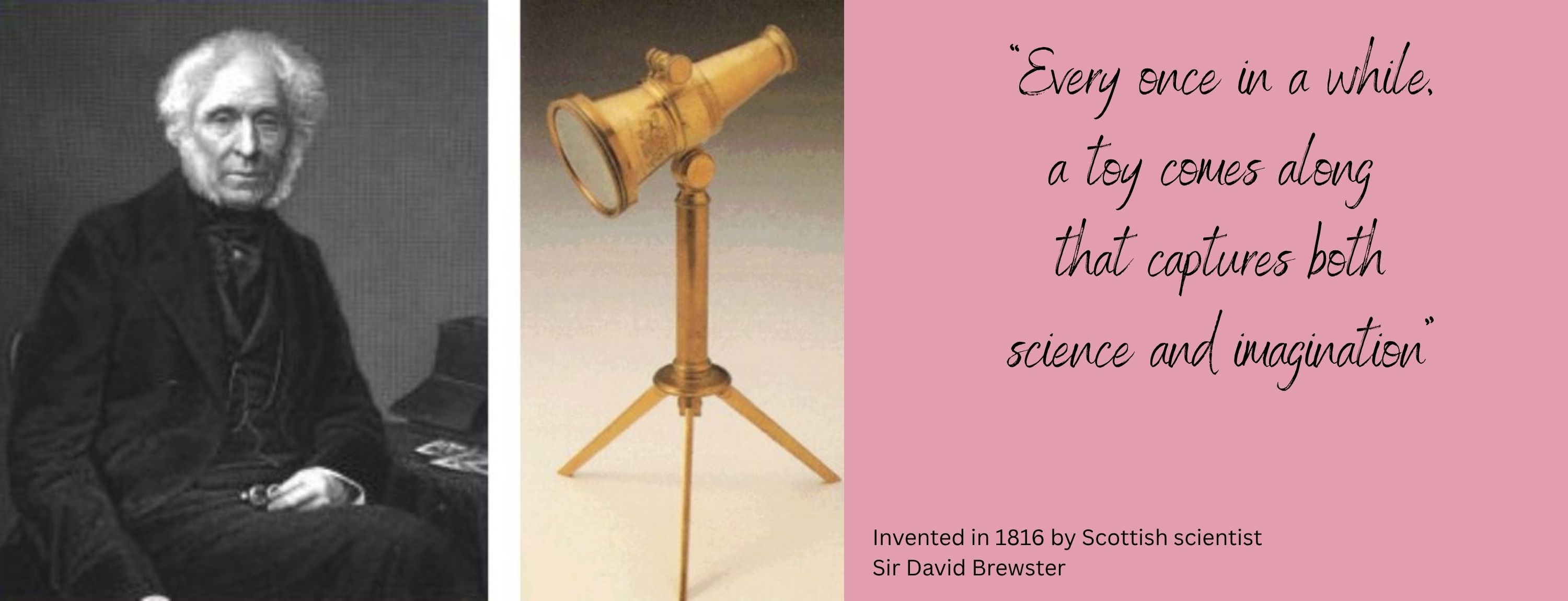

Invented in 1816 by Scottish scientist Sir David Brewster, the kaleidoscope didn’t begin as a toy at all. Brewster was studying the behaviour of light and reflection when he discovered that mirrors and fragments of coloured glass could create endless symmetrical patterns. When the tube was rotated, these reflections shifted and danced — a mesmerising effect that delighted everyone who saw it.

The name itself comes from Greek: kalos (“beautiful”), eidos (“form”), and skopeō (“to look at”) — quite literally, “to look at beautiful forms.”

Brewster patented his invention in 1817, but an error in the patent wording allowed other manufacturers to reproduce it freely. Within months, hundreds of thousands of kaleidoscopes were sold across London and Paris — with little credit or profit returning to the inventor himself.

Despite the setback, the kaleidoscope became one of the first global toy sensations of the 19th century. It enchanted both adults and children, offering a magical glimpse into the science of symmetry and light. For many, it was the first time science had felt like wonder in their hands.

By the Victorian era, kaleidoscopes were being made from brass and fine glass, often given as gifts or used in industrial design. Artists and manufacturers drew inspiration from the patterns they produced, using them to design china, carpets, and fabrics.

In later decades, as manufacturing evolved, kaleidoscopes transformed into colourful tin and plastic versions like the ones in the first image from our collection. One example from our own collection — the 1960sZooscope by Green Monk Ltd. — captures the playful mid-century spirit of educational toys, bright and whimsical while still rooted in science. Click link below to descover more on this artefact.

While the kaleidoscope remains a beloved childhood toy, it has also become a work of art in its own right. Modern makers craft exquisite pieces from stained glass, ceramics, and gemstones, turning them into collectible art objects admired by adults as much as children.

Contemporary variations include:

• Teleidoscopes – Instead of tiny objects inside, these use a lens to transform the outside world into kaleidoscopic patterns.

• Liquid-filled wands – Filled with glitter or beads floating in coloured fluid, they create a slow, drifting dance of light.

• Object wheels – Rotating attachments that let the viewer change designs with a simple turn.

At its heart, the kaleidoscope works on a simple principle of reflection and symmetry.

Inside the tube, angled mirrors (usually at 60°) reflect small fragments of glass or coloured materials. Each reflection forms a repeating geometric pattern — six reflections for 60°, four for 90°, and so on.

This perfect balance of art and physics is what makes the kaleidoscope so enduring: it’s simple enough for a child to enjoy, yet sophisticated enough to inspire scientists, artists, and dreamers alike.

With love

Shyloh

Tales from the youngest daughter of adoll collector — raised on Milo, Vegemite, and more antiques than a country opshop.